What You Should Know About Municipal Water Before Buying A House

We take water for granted. Water for drinking, washing clothes and dogs, showering, cooking spaghetti, and growing spaghetti squash. Sometimes water comes from a well and sometimes from a bottle. But for most of us, most of the time, the water arrives in our taps and showerheads as if by magic. Of course, it's not magic. It's usually our city or town's municipal water supply. It arrives safe and clean thanks to technology and infrastructure, not magic, and most of the time, it all works out just fine, as per the Drinking Water Research Foundation (DWRF). It seems safe, so it's easy to take for granted.

When you're buying a home, it's the right time to stop taking things for granted and get everything as safe and stable as possible. Suppose you have municipal water (rather than a well, or some elaborate rainwater catchment your future neighbors keep mentioning in concerned tones). In that case, you should know where it's from, whether it has encountered any contamination along the way, and what was done about it. You might want to know if the water was recently treated sewage. And, if it was, you should probably know that it's quite a bit safer than most well water (via Wired). And you certainly need to see if you have to install a bunch of equipment in your new home or budget for a huge bottled water bill. Here's everything you should know about municipal water before buying a house.

Water, water everywhere ... but why?

So what's all this water for? Drinking water drives much of the complicated business of water delivery, even though it makes up less than 1% of residential water use. That 1% is pretty important, though, given that our bodies require that we be 100% hydrated to work properly, as per the International Bottled Water Association.

Hygiene uses as much as 80% of your household water, at least if you're in an urban area (via American Geophysical Union). In the West and in cities, outdoor uses can take up as much as 64% of your water. We use more water during the summer, watering lawns and gardens, and we use more in winter than spring by running water to keep pipes from freezing.

We do all this very casually, but there's no guarantee the water will always be there. Future water shortages aren't theoretical; they are a certainty because they are already happening (via Newsweek). So it's worthwhile to get a handle on how and why we use as much water as we do. Each of us uses, on average, 82 gallons of water per day at home alone (via Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)). It's a huge part of our lives.

But wait, there are other water uses

There are, of course, other uses, which can be relevant to your home-buying decision. The American Geophysical Union reports that cities focused on economic development will often have high commercial, industrial and institutional (CII) water use rates. This might come into play if you're looking at a home in a small rural town that's growing fast and might not have the infrastructure to keep up. But bear in mind that a large, water-intensive industry generally has its own water supply. Municipal water uses (golf courses, swimming pools, sports fields, gardens/parks, firefighting, road cleaning, etc.) can use a lot of water, but cities tend to account for this pretty well when planning.

We also use a lot of water indirectly (via Water Footprint Calculator). That's what a lot of that CII water use is. Water is used to refine gasoline, to the tune of about 1 gallon of water per six miles driven. In fact, essentially all power except solar and wind power requires water to produce. Water is used to make almost all goods, especially food. Note that recycling dramatically reduces the water needed to make paper, plastic, bottles, and cans.

Where does drinking water come from?

To understand how safe and plentiful the water in your home is likely to be, you have first to understand where the water comes from in the first place. Most public water systems (91%) are supplied by groundwater, generally pumped from wells. However, more people (68%) are served by systems that get their water from surface sources such as springs, lakes, and streams, as per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). A vanishingly small percentage comes from collected precipitation.

Then there's potable water reuse, which comes in two flavors: indirect and, less commonly, direct. Indirect potable water reuse (IPR) is when a wastewater treatment plant releases treated sewage, stormwater, etc., into public waterways or the ground, for later incorporation into a municipal water supply (via American Water Works Association). There are other purposes for this reintroduction of treated water, like buffering against salt buildup. However, direct potable reuse (DPR) describes a process by which treated water is directly introduced to the water supply, and only happens in a few states such as California and Texas.

Where are you, and where's your water?

The sources of our water matter because the challenges in supplying safe water depend, to some extent, on the source of that water. The New York Times reported that in the past 40 years, as much as 10% of U.S. water systems have failed to meet Safe Drinking Water Act requirements, leaving tens of millions of people exposed to unhealthy contaminants.

Emerging concerns such as PFAS contamination apply to both ground and surface water (via Association of Metropolitan Water Agencies (AMWA)). But pharmaceutical contamination, while it applies to both sources, is of far more concern when found in groundwater because it makes up a large percentage of drinking water, yet isn't treated as aggressively (via AMWA). The concern is real: Wells in Sweden have been closed due to high PFAS levels (via National Library of Medicine). And while some problems are environmental, we must still take them seriously. For example, the presence of antibiotics in the water supply leads to antibiotic resistance, which is bad for everyone (via National Library of Medicine).

Urban versus rural water supplies

It's natural to assume that water from areas with rolling hills and beautiful streams is better than water from the land of parking lots and manmade everything. But a 2018 study showed that low-income rural regions are the most prone to expose citizens to contaminated drinking water. New programs focused on rural water and water equity issues promise to address this imbalance, but that won't happen in time to address your new home worries.

Also, a recent program has emerged to map and begin planning for the removal of lead water service lines in 45,000 small and rural communities (via EPA). And a project by Tap Score uses data about the age of homes and the corrosiveness of water throughout the country to determine and map the likelihood of lead in drinking water, so it's probably worth a look to make sure the rural home you're buying isn't at high risk.

How is water treated?

There are several water treatment methods, and each is useful for dealing with particular water quality issues. While the University of Wisconsin-Madison notes it's hypothetically possible to remove many prevalent contaminants given unlimited time and resources, what matters to you if you're buying a home today is what is actually being removed from (and being left in) the water supply. The average treatment plant could only clean water of about half the drugs in one particular study, and research suggests that removing more than 75% of a particular chemical is exceedingly difficult except where specialized facilities are available (via Scientific American). Certain industries, such as natural gas/fracking and pharmaceuticals, tend to generate contaminants that are more difficult to remove, either because of technical limitations or the sheer quantity of pollutants.

Understanding the basic methods of treating water is very straightforward (via CDC). The two key methods, filtration and disinfection, are actually categories of many specific methods. Filtration systems are probably the most recognizable to the public. These include filtering through a medium and ion exchange, reverse osmosis, and others. Disinfection is the process of adding chemicals to the water to remove or neutralize threats and concerns. These are the cornerstones of both municipal and home water treatment.

Treating city water like gold

According to the CDC, municipal water treatment uses particular large-scale varieties of these treatment strategies, while home treatment systems will use smaller (but often more effective) versions. A process unpleasantly called some combination of coagulation/flocculation/sedimentation involves unpleasantly chemically combining contaminants into unpleasant larger pieces, which are then separated from the water via the sedimentation process. This removes the bulk of contaminants in a pleasant drinking water supply.

Next, the water is filtered by a variety of media based on the conditions and demands of the local water supply (via United States Geological Survey). Finally, disinfection (often in the form of chlorine or chloramine) is then used to kill any remaining bacteria, viruses, and parasites in the water, as well as protect the water from further contamination while en route to your home.

It's important to note that parts of this treatment process happen when wastewater is released into the water supply from residential or commercial uses, and other parts are used when (the same or different) water is collected and treated for use.

Treating water in the home

Perhaps because the bulk of the work has been done by treatment plants, home water treatment methods can produce clean, safe water, as per the CDC. There are two basic types of water treatment in the home: point-of-entry and point-of-use. Point-of-entry treatment addresses water for use in the whole house, or at least in multiple outlets within the house. Point-of-entry treatment is applied to every use of water that isn't specifically and physically excepted from the process. On the other hand, point-of-use treatment improves water at a particular faucet (such as a dedicated drinking water tap) or appliance (such as an ice maker).

Most treatment technologies are available for both point-of-entry and point-of-use scenarios. There is often a big difference in cost. For example, a whole-house (point-of-entry) reverse osmosis system costs between $12,000 and $20,000 (via Fresh Water Systems), while a point-of-use RO system ranges from $150 to $1300 (via HomeAdvisor).

Typically, home water treatment systems consist of some combination of filtration (including common and elaborate reverse osmosis mechanisms), distillation, disinfection, and water softening. Reverse osmosis tends to be the most common method that delivers the most complete, effective results. But note that the World Health Organization (WHO) claims there are a number of negative health effects of drinking demineralized water from RO systems, from missing critical minerals in your body to the accumulation of toxic metals.

What are we treating, anyway?

Water contaminants are numerous and very common, so it's difficult to consider them all at once. Take drugs alone: According to Springer Nature, there are reports of at least 93 pharmaceutical compounds present in drinking water sources. In addition to pharmaceuticals and the emerging concern over PFAS, runoff from farms might introduce pollutants such as nitrates, phosphorus, organic matter, and pathogens, including protozoa, bacteria, viruses, parasitic worms, and fungi. Tasty!

According to the Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources in UNL, these come from many sources: Runoff from lots and farms; leaching through the soil (particularly from landfills); and leaky well casings, to name a few. Look around your potential new home. Are there likely culprits such as open lots, intensive animal feedlots, or a landfill? The more you know, the more you'll know what questions to ask.

The Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) requires the regulation of more than 90 contaminants known to occur in drinking water, and the EPA has a program (UCMR, the Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule) that keeps an eye on pollutants that are currently unregulated, but are known to occur in water sources and might represent a case for future regulation. If you're interested in consulting this data regarding your future home, summaries, instructions, and data can be downloaded from the EPA website.

So how do you find out about water quality?

Knowing what to look for is important, of course. An urban area with lots of industry or a rural area that's likely to have lots of agriculture-related runoff of herbicides and pesticides should put you on high alert. Talking to neighbors is always a source of interesting information. In both cases, what you learn is unscientific at best.

According to DWRF, your most reliable tool when trying to suss out the water quality in a particular municipal supply is to consult the system's Consumer Confidence Report (CCR). These are detailed reports that municipal water systems must distribute to the public each year by July 1. CCRs list levels of contaminants, including residual disinfectants (such as chlorine or chloramine), as well as information about the health effects of these contaminants and the actions your water supplier is taking to correct the problem.

The EPA maintains a site where these reports are supposed to be available, but note that the results can be spotty. For example, only 35 of the 2,379 possible reports for the state of Georgia are available on the EPS site. So you might need to contact your municipal water system directly.

Concerned yet? Well, no pressure

When evaluating the municipal water supplying your potential home, water safety isn't the only concern. Because U.S. water supplies are generally very safe, many of us become concerned with less urgent matters of water use and quality. Perhaps the one that most directly affects people the most often is water pressure.

This Old House reports home water pressure should be between 40 and 60 psi. High water pressure can be dealt with by installing a pressure-reducing valve, which your home might already have near your water meter (via This Old House). Low pressure is more complicated and might be addressed by adjusting the pressure-reducing valve. If that doesn't work, compare notes with neighbors and inquire with your water supplier to find the source of the issue. If all else fails, you can install a water pressure booster. Note that this is not work for a casual DIYer and can cost upwards of $2,000, including labor.

Hard water and water softeners

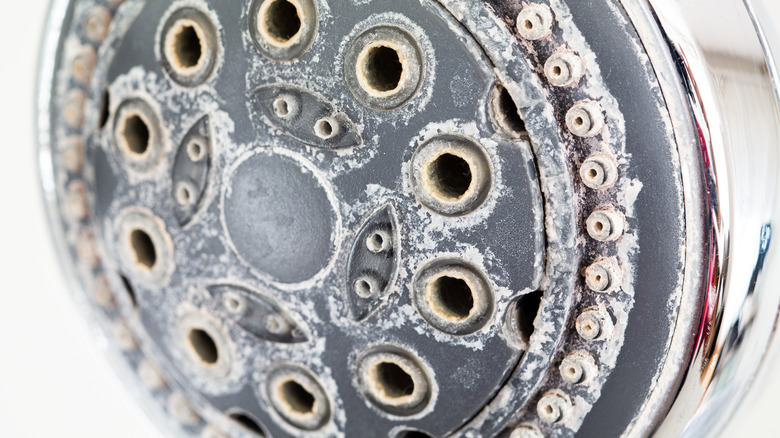

"Hard" water is the presence of particular minerals that cause problems for homeowners, notably scale, which can clog pipes and damage appliances. If the home you're considering doesn't include a water softener loop (a length of exposed pipe to which a water softener appliance can be attached in the future), make sure the space will allow for adding one easily, as per American Home Water.

Another type of plumbing loop to watch out for in your new house is a bypass loop, which is an arrangement of valves that allows you to temporarily bypass a plumbing appliance such as a whole-house water softener (via GE Appliances). Many water softener units include an integrated bypass valve, but this isn't useful when installing or replacing the unit itself.

Water softener devices tend to be surprisingly pricey, and beware if you're considering a salt-free system. While these water conditioning devices can be cheaper than water softeners, they do not remove the substances that cause scale and do not effectively or efficiently soften water (via Discount Water Softeners).

Well, how about a well?

According to the CDC, 15% of people in the United States use individual water supply systems (usually various types of wells, and occasionally cisterns or springs). The first thing to know is the type of well you are considering or is already installed in your potential future home. Shallow dug wells and driven wells, which are hammered into the ground, are especially prone to contamination. At least 919,000 dug wells are in operation in the U.S., and many are improperly maintained (via CDC). Wells with high-risk factors (runoff, close proximity to buildings, unfiltered water intrusion, shallowness, etc.) require expert inspection because water quality in these wells can change in a matter of hours, rendering a single water test with no context almost useless.

If you're thinking of adding a well to a property, contact your local health department to determine if wells are allowed for your community or home. If so, it's important to familiarize yourself with preparations and maintenance issues related to operating a well safely.

So, what else do I need to lose sleep over?

These are not, by a mile, the only water quality concerns you might take into account, says the CDC. Many of the issues are larger environmental problems and not as likely as other problems to directly and immediately influence your family's health. The term "water quality" also addresses temperature, acidity, levels of dissolved oxygen, turbidity (cloudiness), specific conductance (a measure of possible contamination), suspended sediment, and many other attributes (via Michigan Sea Grant). There is a lot to look at here.

You will also, of course, factor in your personal preferences. If you're not particularly concerned about pharmaceuticals in your city water supply, that quality aspect isn't really much of a quality issue for you. The trick is to know which things you care about, and then find out if the municipal water in your next home scores well in those areas.