The Untold Truth Of Frank Lloyd Wright

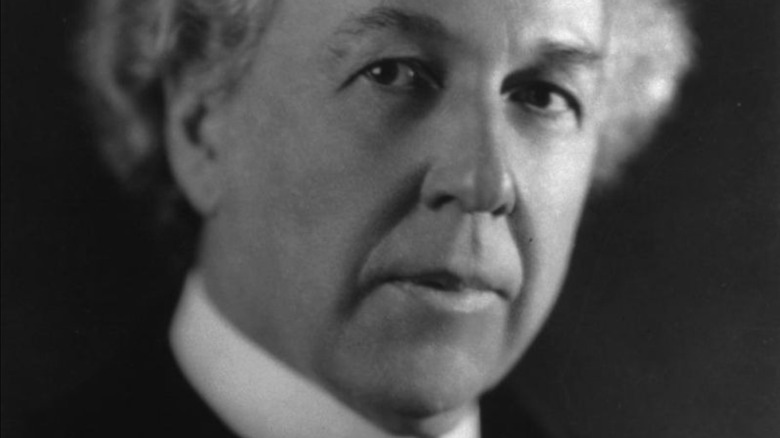

If you're not an individual who is interested in the nuanced composition of bricks and mortar or who gets excited by the aesthetic and innovation of a well-designed roof, chances are you cannot name all that many architects. Nevertheless, you're probably familiar with the name Frank Lloyd Wright, and for good reason. The man described by the American Institute of Architects as the "greatest American architect of all time" is much more than just an obscure Simon and Garfunkel song – he designed some of the most iconic buildings to ever grace our flowering civilization. Yet, to simply describe Wright as an architect is like calling The Beatles a boy band who wrote a few good tunes. The big daddy of design didn't just create buildings that would stand the test of time; he believed he was conducting symphonies made of stone.

If the building trade had a Mozart it would be our Frank. His legacy and artistry are everywhere, from the Guggenheim Museum in New York to Fallingwater in Pennsylvania. In his own words the architect's role was to "help people understand how to make life more beautiful, the world a better one for living in, and to give a reason, rhyme, and meaning to life." It's a bold mission statement, but Wright was no garden variety architect. As with many geniuses his personal life often overshadowed his works, so let's open the elaborately designed front door on the untold truth of Frank Lloyd Wright and take a peek.

Frank Lloyd Wright was a great and reckless spender

Oscar Wilde once wrote, "Anyone who lives within their means suffers from a lack of imagination." It's a quote that poignantly applies to Frank Lloyd Wright. The great architect may have believed in pushing the envelope and thinking outside of the box, but he wasn't all that shrewd when it came to counting his pennies. According to Wealthy Genius, Wright designed more than 1,000 buildings during his 70 year career and was worth $25 million when he died of a heart attack in 1959. Unlike other boundary-breaking iconic artists such as Mozart and Van Gogh, who died dirt poor and deadbeat, Wright left this mortal coil as a financial success. This is surprising because according to Peter C. Alexander's book, "Insufficient Funds: The Financial Life of Frank Lloyd Wright" (via The American Law Institute), the architect's reckless spending habits led to a life of financial instability.

Wright loved luxury, and he had a particular passion for Japanese art, cars, and pianos. He may have used his god-given talent with a measuring tape and drawing board to create a series of jaw-dropping and gravity-defying buildings, but alas he was a mere mortal who loved to shop. Wright's extravagant spending often entailed he had insufficient funds to cover his living expenses. Yet the man was busy creating monuments that would last for centuries, and why else were creative accountants created if not to enable spendthrift mavericks like Wright to live largely and free?

Frank Lloyd Wright published over 20 books

Writing one book is a huge undertaking, but writing over 20 takes a certain stamina and strength of spirit, especially when your primary occupation is designing iconic buildings. To be fair, we're not talking Stephen King style bestsellers here, and the books are all a bit niche but it's still an impressive output. You can find them all on Goodreads, and with titles such as "The Future of Architecture," "Organic Democracy," "The Natural House," "The Living City," "The Disappearing City," and "When Democracy Builds," it's apparent that all Frank Lloyd Wright's literature shares the common theme of design. He even penned a children's book called "My First Shapes with Frank Lloyd Wright" to foster a love of architecture in the minds of little ones the world over.

According to Famous Homeschoolers, Wright's writing career took off after the stock market crash of 1929. After becoming bankrupt, he returned to his childhood home and wrote his autobiography during the Great Depression. Published in 1932, it would act as an innovative form of advertising and the architect's star was in the ascendancy again.

Writing books came naturally to Wright. He loved to learn and loved to teach. His father taught him to become versatile on the piano, violin, and cello at a young age, and The Taliesin Fellowship Wright founded believed that studying Shakespeare and the rhythms of nature were as vital to the profession as architecture as the fundamentals of design.

Frank Lloyd Wright was a fierce individualist and lifelong outsider

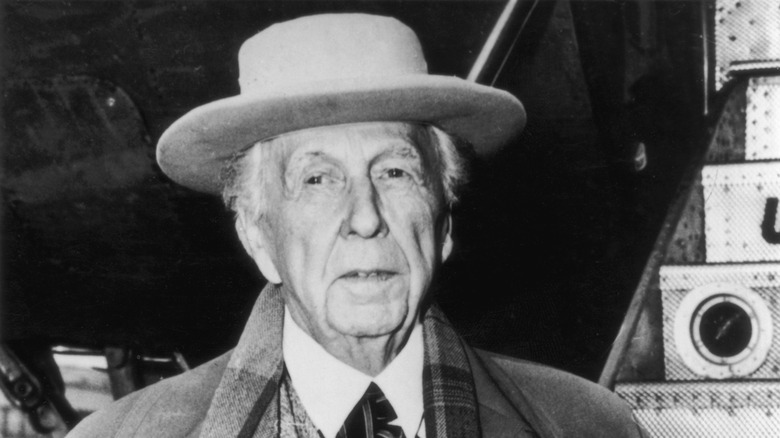

Swimming against the tide and marching to the beat of a different drum doesn't just encourage creativity, it often defines it. Frank Lloyd Wright took his role as the black sheep of the flock seriously. According to Architect magazine, Wright was perpetually on the outside looking in when it came to the architecture business. The man himself once said, "My way has been too long and too lonely to make a belated bow to my people as a modern architect." Strange words from one of America's most celebrated visionaries, but Wright often butted heads and locked horns with establishment figures like the American Institute of Architects (AIA), who described him as a "lone wolf not prone to joining associations."

According to Architectural Digest, even though the AIA recognized him with its gold medal in 1949, Wright adamantly refused to join their ranks explaining that "architects are all that's wrong with architecture." He was described during his life as a man not part of the crowd, but ahead of it, and if the crowd included architects he'd stay as far away from it as possible. Wright described modern architecture as "servile insignificant refuse." It's probably safe to say he had a lofty disdain for most other T square and triangle men!

Frank Lloyd Wright's mother predicted he would design beautiful buildings when he was a baby

Every adoring parent believes their precious baby has the unlimited potential for world-beating greatness. Yet it's usually a vague, ill-defined notion inspired by the miracle of birth and wonder of youth. Yet Frank Lloyd Wright's mother was cut from a different cloth. If she viewed her son as a sort of architectural Jesus Christ, then she cast herself in the role of John The Baptist. Anna Lloyd-Jones actually predicted that her son would transform the face of architecture and did everything in her power to set him on the right path. According to Famous Homeschoolers, the pushy mom lovingly adorned the walls of little Frank's nursery with stunning cathedrals until the penny subliminally dropped in his youthful mind.

Lloyd-Jones also ensured her son spent a lot of time playing with a special set of geometrically- shaped educational blocks created by kindergarten founder, Friedrich Froebel. The blocks were of varying sizes and could be used in a multitude of combinations to create three-dimensional and innovative creations. Did these blocks lay the foundation for Wright's lifelong love of symmetrical innovation and geometrical transcendence? Or is it all just a happy coincidence magnified through the beneficial lens of hindsight? In his biography, Wright would often play upon the riff about his dear old mom being the first to recognize his unmistakable genius when he was still in diapers, but then again modesty was never his strongest suit.

Frank Lloyd Wright was deeply inspired by Japan

Frank Lloyd Wright may seem as American as apple pie, but he was deeply influenced by, inspired by, and in love with Japanese culture. According to The Frank Lloyd Foundation, he was devoted to the idea of architecture as "the great mother art, behind which all others are definitely, distinctly and inevitably related." Wright believed it was right of everyone to live a beautiful life in a beautiful environment, and believed above everything that was an architect's true calling. The Japanese cultural philosophy that all objects, humans, and actions can be profoundly integrated and transform an entire civilization into a precious work of art appealed to Wright's desire to create an underlying unity in his work.

According to Smithsonian, Wright's interest in Japanese art began in his early twenties. Fast forward ten years and he was a world-renowned collector of Japanese woodblock prints. The influence from the land of the rising sun also seeped into Wright's work, and the face of modern American architecture was changed forever. According to KCP International, Wright cited Japan as one of the biggest influences on his life alongside his childhood building blocks and mentor, Louis Henri. Wright first visited Japan in 1905, and as the architect of Tokyo's New Imperial Hotel he lived there for three years between 1917 and 1922. The hotel survived the Great Kanto earthquake of 1923, but could not survive the uncompromising dictates of urban development and was demolished in 1968.

Frank Lloyd Wright had multiple romantic relationships throughout his life

The following material mentions homicide.

Frank Lloyd Wright was passionate about bricks and mortar, but he also held something of a flame for the fairer sex. According to HowStuffWorks, Wright met his first wife, Catherine Lee Tobin, nicknamed Kitty, when he was an ambitious draughtsman at a Chicago architecture firm. The couple would remain married for 20 years and had six children together before Wright met a client named Mamah Borthwick Cheney and got itchy feet. Wright abandoned his wife, kids, and practice in 1909 to elope to Europe with the married woman and caused a national scandal.

Back in the States, Wright set about building a home in 1911 to celebrate his new union; it was named Taliesin after the legendary Welsh poet. Tragically in 1914, a servant called Julian Carlton allegedly murdered Cheney and her two children, before burning the house to the ground.

Wright threw himself into rebuilding Taliesin and hooked up with high-class spiritualist Maude Miriam Noel. When Wright's divorce to Tobin was finalized in 1923, he married Noel, but their rocky relationship didn't last. After six months of marriage, he was bedazzled by ballet dancer Oligivanna lvanova Lazovich. The path of true love may not run smooth but it's built to last. Wright and Lazovich married and had a daughter together. They only separated upon Wright's death at the age of 91 in 1959.

Frank Lloyd Wright believed in sustainability before it was a thing

In the era when Frank Lloyd Wright was designing and building, the impact of human-made buildings upon the natural environment was a topic about as hot as the exact measurements and material angels' wings were made from. In other words, sustainability was not high on the agenda. Yet, as in so many other things, Wright was dancing to a different tune. According to The Frank Lloyd Organization, the great architect believed his trade should be one of integrity and commented, "Buildings like people must first be sincere, must be true," in order to nourish the lives of those living within them. It's a completely different sentiment to the "stick em' up fast, stick em' cheap" philosophy behind much modern house building.

Wright's guiding principle was that buildings should be in harmony with their time and place. "In organic architecture then, it is quite impossible to consider the building as one thing, its furnishings another and its setting and environment still another," he explained. "The spirit in which these buildings are conceived sees all these together at work as one thing."

For a physical embodiment of this idea, look no further than Wright's famous Fallingwater house and garden, built in 1936. The Culture Concept reports that the design symbolizes Wright's instinctive grasp of the philosophies inherent in Taoist Zen Buddhism. Wright also insisted that stone from a local quarry and wood from nearby woodland were used in its construction.

Half of the buildings Frank Lloyd Wright designed were never built

It's tempting to think of all the great bands who split up before all of their songs were written, all the inspired writers who hung up their pens before the ink was dry, and all the disillusioned artists who turned their backs on unfinished masterpieces and wonder what could have been. Do classic songs remain unsung, definitive books remain unwritten, and great buildings remain unbuilt because, in reality, they wouldn't have been all that great? According to Architectural Digest, Frank Lloyd Wright designed over 1,100 structures during his lifetime, but a staggering 660 of them remain unbuilt, unrecognized, and destined to spend eternity on a shelf, gathering dust in obscurity.

However, Wright fans can now catch a glimpse of just how majestic these buildings might have looked thanks to a labor of love by Spanish architect David Romero. In partnership with the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Romero has used Wright's sketches and blueprints to render Wright's unrealized masterpieces in all their innovative glory. Technology and its tools have now given us glimpses of what innovative designs such as the Butterfly Wing Bridge in San Francisco and the Larkin Administration Building in New York would look like. Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation President Stuart Graff explained, "While we will never know the true experience of visiting an unbuilt Wright design, these renderings can convey a bit more sense of space and light than the drawings alone."

Frank Lloyd Wright nearly built the world's tallest building

Frank Lloyd Wright did a lot of great things in his nine decades on planet Earth, but one thing he didn't quite achieve was to build the world's tallest building — but he nearly did and that counts for something. According to The Lyncean Group of San Diego, on October 16, 1956, when he was a sprightly 89 years old, Wright introduced the world to what could potentially be its tallest skyscraper. The Illinois Mile-High Tower was a thing of beauty whose tripod spire was planned to grace the city of Chicago. Standing at 1,609 meters with 528 floors, the Illinois was four times bigger than New York's Empire State Building and was intended to free up ground space by eradicating the need for other skyscrapers in the neighborhood.

The Illinois would be built according to Wright's distributed urban planning concept that he named Broadacre City. From the mid-1930s to his death in 1959, Wright was a fierce advocate of the belief that instead of spreading outwards, urbanization should always spread upwards. By utilizing more than seven times the gross floor area of the world's then-tallest building, the New York Empire State Building, and three times more than the Pentagon, Wright believed the Illinois, with a capacity for 100,000 occupants, could house all government offices in Chicago under one roof. Unfortunately, the size of this project proved too big for Wright to handle and it slumped instead of soared.

There was a mass murder at Frank Lloyd Wright's Taliesin estate in 1914

The following material mentions homicide.

After moving from Alabama and securing employment as a servant at Frank Lloyd Wright's Taliesin Estate, it only took Julian Carlton six months to tender his resignation. Yet before he hit the road, Carlton's last act was to serve a meal to Wright's mistress, Mamah Cheney, and her children on the patio of Taliesin, per the Daily Mail. As the family ate, Carlton disappeared into the house and reportedly returned with a hand ax, and murdered Cheney in front of her horrified children. Carlton would go on to slaughter both children as well.

Carlton would subsequently set fire to Taliesin and allegedly kill four workers who were lodging on the property. He would die in police custody months later with no one any nearer as to why he had committed murder. The Washington Post reports that the carnage was considered by many of Wright's critics as revenge for his cheating. Yet, the real reason for Carlton's bloody rampage remains a mystery. In his book "Plagued By Fire," author Paul Hendrickson explores all avenues but comes up with little tangible evidence as to what drove Carlton to kill. Upon hearing news of the tragedy, Wright was reported to have stayed up through the night, playing Bach on the piano and weeping softly for life and love lost.

Frank Lloyd Wright loved to collect cars

Frank Lloyd Wright liked to live life in the fast lane in more ways than one; he also loved the sublime aesthetic of a well-designed car. For Wright, something that was practical should also be a work of art and vice versa. To that end, Wright liked statement buildings and he also liked statement cars — hence his infatuation with a well-built automobile. Wright purchased his first car in 1909, as noted by Petrolicious. The Stoddard-Dayton K5, nicknamed "The Yellow Devil," had a max speed of 60mph and was something of a speed demon for the era.

Wright, like most of his generation who experienced the newness and invention of the car, was spellbound by its might and majesty and could be found tearing around Illinois in driving goggles and a linen suit. After being bitten by the automobile bug, Wright was consumed by a passion for all things four-wheeled to the end of his days. It's reported that he owned 85 cars throughout his lifetime, and he was rumored to have a particular fondness for Jaguars. Wright's love for cars often spilled over into his work, too. In an age where most houses didn't have a garage, he would design projects with entire ground floors dedicated to storing automobiles. In fact, it was Wright who first came up with the idea for a carport.

Frank Lloyd Wright was reportedly the inspiration for Ayn Rand's The Fountainhead

In his 1889 essay "The Decay of Lying" (via The Westologist), Oscar Wilde opined that "life imitates art far more than art imitates life." That may well be, but in the case of Ayn Rand's novel "The Fountainhead," the fictional architect, Howard Roark, is a dead ringer for Frank Lloyd Wright. According to The New York Times, "The Fountainhead" is Rand's "hymn in praise of the individual," and opened the ears of a new generation to the siren call of architecture (via Arch Daily). The late Lebbeus Woods stated that Rand's book "had an immense impact on the public perception of architects and architecture, and also on architects themselves."

Novels with architects as their chief protagonists are admittedly thin on the ground, but the plot of "The Fountainhead" rectifies that in fine style. It revolves around Roark's fierce individualism and his heroic insistence to succeed on his terms. It is about a man with vision who believes in burning down the dogma and dullness which handicaps his peers and blazing a trail into a bright and bold future where anything is possible. It's also quite literally about an architect's sacred and God-given right to order a building to be demolished if it's ugly and offends their artistic taste. Just as writer Manley Halliday said that Budd Schulberg's "The Disenchanted" is the literary embodiment of F. Scott Fitzgerald, Roark is unmistakably Wright writ large.