We Tried Dehumidifying A Kitchen With Charcoal And The Hack Was Full Of Hot Air

"Humid kitchen? Charcoal will soak it right up!" Sometimes the frustrations of life simmer gently in the background, and sometimes they boil over, steaming up the walls and windows and causing water to drip from the ceiling like a humidifier run amok in a closed-up RV. When we saw, for the thousandth time, people being advised to dehumidify their kitchen air with a bowl of charcoal, we finally hit the steamy window stage. This myth has an epic following at this point with no end in sight. Professionals with a reasonable understanding of air quality are even repeating it now. And it turns out not to be true.

Google returns 3.3 million results for the query "charcoal reduces humidity in kitchen" (without quotation marks), and 782,000 matches when doing a verbatim search. We sampled dozens of the top results to see how many were repeating this claim, including Google's generative AI articles. Excluding forums like Quora and Stack Exchange, all of the results we saw reported this capability incorrectly.

Interestingly, at least one person on every forum we looked at seemed to debunk this notion. Of course, these lone voices crying in the internet wilderness don't have a chance against the growing masses with their fruit bowls of charcoal briquettes and hidden patches of mold steadily growing inside their vent hood covers, to say nothing of the generative AI parrots. Instead of just adding our voice to the dissenting crowd, we decided to try to prove our point.

Setting up a charcoal dehumidification test

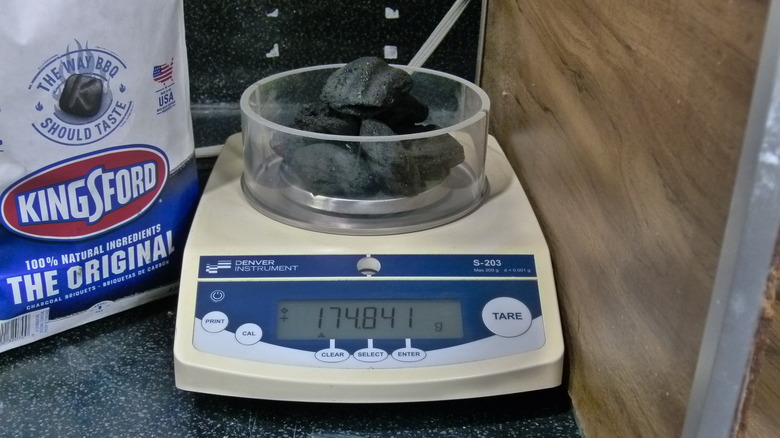

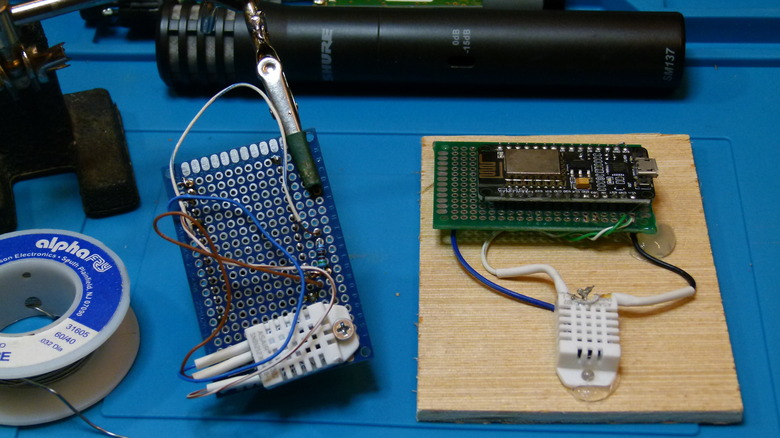

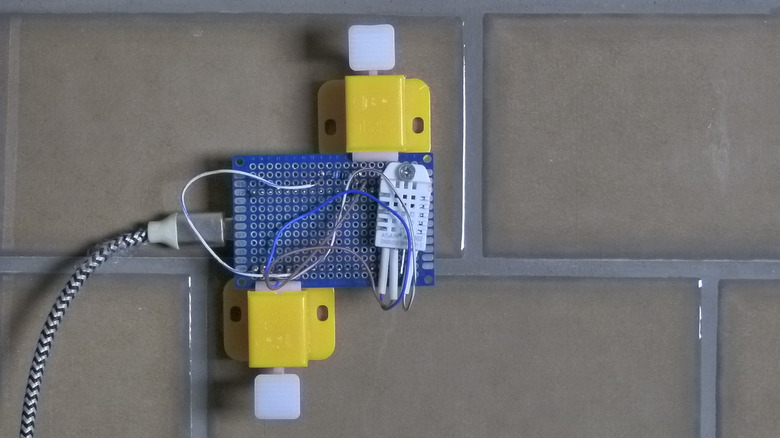

We put carefully weighed Kingsford Original charcoal briquettes, a hardwood charcoal with no chemical additives that might affect our results, into three commercial steam table pans. Each held a slightly different form of the charcoal: one with briquettes straight from the bag, one with briquettes smashed up coarsely with one mallet blow per briquette, and one with briquettes (also smashed) that had spent 24 hours in a cabinet dehydrator on its high setting. To this party, we brought three humidity sensors — two homemade devices with WiFi-capable microcontrollers that we programmed to record sensor data and a commercially available Lüft indoor air quality monitor ($249). A little later on, we also employed a 50-pint Zenith electric dehumidifier for comparison.

The steam table pans represent three things: the product as you might buy it, the product smashed to increase its surface area (hypothetically improving the amount of water the carbon could adsorb), and the product with as much humidity as possible removed to give it a fighting chance to adsorb whatever it could from our kitchen. We took readings every two minutes, and the Lüft recorded data every six minutes. We ran the setup for four days (plus a 12-hour power outage) — 24 hours with no charcoal or dehumidifier, 24 hours with only charcoal, 24 with only the electric dehumidifier, then 24 more with neither.

(Over)engineering proof of the obvious

There's a corner of our workshop jokingly called "the lab," where we've tested a number of products and ideas. In spite of the Denver Instrument scale, a suitcase full of measurement instruments, and a bunch of microcontroller-driven testing gear, it's not really a lab. We don't have the training, infrastructure, or disposition to really test anything scientifically, including this. We'd need to be able to replicate the space of various kitchens and their common humidity inputs and outputs with lots of precision and control. Every time you open the door to the patio, every time the HVAC exchanges air with the outside, every time you boil a pot of water or run the dishwasher, air molecules attempt to diffuse themselves so that they are distributed equally throughout the kitchen ... and when the patio door is opened, with some local portion of Earth's atmosphere.

We controlled what we could by running the dishwasher once per day at a particular time, not running heat or air conditioning for the four-day span, boiling no water at all, etc. The homebrewed sensors were operated at about counter height and their DHT22 sensors are accurate to within 2%, the same as the Lüft monitor. We expected to see slightly higher humidity in these than the Lüft since moist air is less dense than dry air. For an additional data point, we also weighed the three charcoal batches after their work was done.

Charcoal soaking up many liters of water? Don't hold your breath.

When we charted out the kitchen humidity over the four days of our test, the gentle ebb and flow of moisture in the air were only affected when we put the electric dehumidifier into service... and then only a little. (But electric dehumidifiers are very useful in rooms like pantries that are more closed off than the typical kitchen.) The charcoal in our three steam-table pans actually lost mass along the way, probably in the form of charcoal dust dropped when transferring the charcoal from container to container. If so, the dust apparently weighed more than the water the charcoal adsorbed. The pan that spent 48 hours in our cabinet dehumidifier actually did the worst by a small margin. This doesn't mean the charcoal didn't adsorb any water; it probably simply re-evaporated when the humidity was low since a bowl or a steam table pan has no mechanism for preventing that evaporation.

In any event, it's clear that simply opening a bag of charcoal and plopping some briquettes into a bowl wasn't going to do any good. You'd probably have more effect on the humidity of a room by holding your breath while in it. Of course, we knew from the beginning that this was never going to work, joining TikTok's charcoal hack to keep cut flowers fresh in the myth circular file. Let's take a quick look at why.

What the science and the charcoal manufacturers say

Activated carbon is a desiccant with a maximum capacity of around 0.41 grams per gram. That means it can't quite "hold" (adsorb) half its weight in water. Activated carbon adsorbs far more water than non-activated, but let's pretend a typical 7.7-pound bag of charcoal is activated carbon. In a perfect scenario, our 175-gram sample could adsorb 71.75 grams of water, and an entire 7.7-pound bag of charcoal would hold about 3.13 pounds of water, around 1.4 liters — so about 35 such bags of charcoal (270 pounds, not "a few briquettes," as some articles suggest) to reach the 50-liter capacity of most home dehumidifiers.

But that's if it worked at all, and desiccants simply don't work in open spaces. Manufacturers are unanimous and clear that their products only work in sealed containers. According to 3D Barrier Bags, for example, desiccants "must be within an airtight sealed package (such as a barrier foil bag)." The Conservation Wiki explains that a desiccant-containing pollutant absorber must be inside a sealed enclosure; otherwise, "the absorber [in a display case] is quickly exhausted because it is, in effect, purifying the air of the entire room." There are as many such statements as there are manufacturers and sellers. An electric dehumidifier might be able to keep up with the occasional influx of new, humid air, but a bucket of charcoal briquettes certainly could not. Charcoal does make a useful mulch and great steaks, though, so all is not lost.